The second conservation priority site we identified was the wilderness portion of the old Boise Cascade property (now coined the St. Helens Industrial Business Park). It made our list as the second-most pristine site for meadow reptiles. The complex supports Rubber Boas, Racers, and one of just three populations of Western Skinks in Columbia County. There is a chance it also houses cryptic Ringneck Snakes, with sightings just a few hundred yards away.

The site also supports a strong wetlands assemblage, with Western Long-toed Salamanders, Rough-skinned Newts, Pacific Treefrogs, and Northern Red-legged Frogs breeding in the vernal pools and stream overflow. Garter snakes are present. The creek is a corridor for Western Painted Turtles as well as salmon and steelhead runs.

But this land’s value goes far beyond the herp and fish assemblage. I’ll start with a bit of Willamette Valley history.

Volcanos, floods, and development

15 million years ago, rivers of lava emanated from a supervolcano in eastern Washington and made their way down the Columbia River Basin. They cooled as they went, transforming into the basalt that underlies much of northern Oregon’s landscape.

A mere 15,000 years ago, a glacial lake in Montana burst through its ice dam, sending walls of water rushing down the Columbia and flooding the tributaries along its path. Then it happened again….and again. These megafloods scoured the basalt in some places and deposited hundreds of feet of sediment in others, giving us the matrix of rock formations and fertile agricultural land that define the Willamette Valley today.

Where minimal topsoil remained, beautiful meadows emerged. The soil wasn’t deep enough for trees to root, so sunlight bathed the ground and wildflowers thrived. The combination of open sunlight and exposed rock kept the ground warm enough for sun-loving snakes and lizards to extend their range northwards. Vernal pools formed in these meadows after rains, attracting their own invertebrate and amphibian communities.

Where soil did build up, the sandy deposits drained well in summer, favoring deep-rooted oaks over the more shallow conifers, resulting in extensive oak woodlands and a unique plant community.

The Native Americans of the Willamette Valley relished these oak-meadow complexes. One of the most common wildflowers was camas, which produces a delicious, nutritious bulb that became a staple. Other meadow plants were used for medicinal and decorative purposes. The oaks provided acorns for food as well as attracting deer, elk, bear, and squirrels to hunt. There appears to have been a Wakanasisi village at Milton Creek on or near this site. The village was displaced in the early 1800s, but in 1855, about 47 Clatskanie and Ne-Pe-Chuck peoples from “peaceful tribes” were moved here as a temporary reservation, before being moved again a year later to the Grand Ronde Reservation.

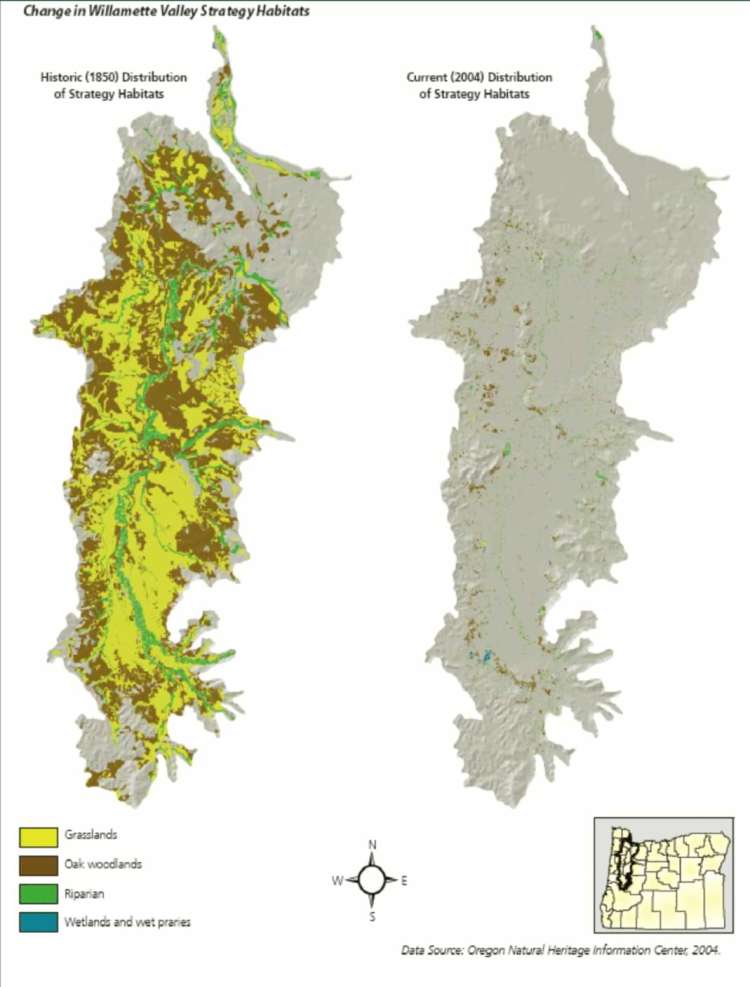

Of course, the Native American peoples were being forced out because the rivers and valleys had become a magnet for development. Where the soil was deep enough, we farmed it, where the rock was exposed, we mined it, and on everything in-between we built our homes and cities. 98% of the oak woodland and meadow habitat in the Willamette Valley was developed, including 99.75% of the camas meadows.

Here in Columbia County, there are very few of the original meadow plots left. And one of the best camas meadows remaining sits adjacent to the old Boise Cascade paper mill.

Nature found there now

We were introduced to the property by Patrick Birkle, our old St. Frederick’s youth group leader from 30+ years ago. From the very first trip, its uniqueness was apparent. We were struck by beautiful basalt formations in damp green woods, and the surprising expanses of meadow held promise. Matt and I made a few finds of our own there. But it was our volunteer, Lucas Green, who truly discovered the value of the place.

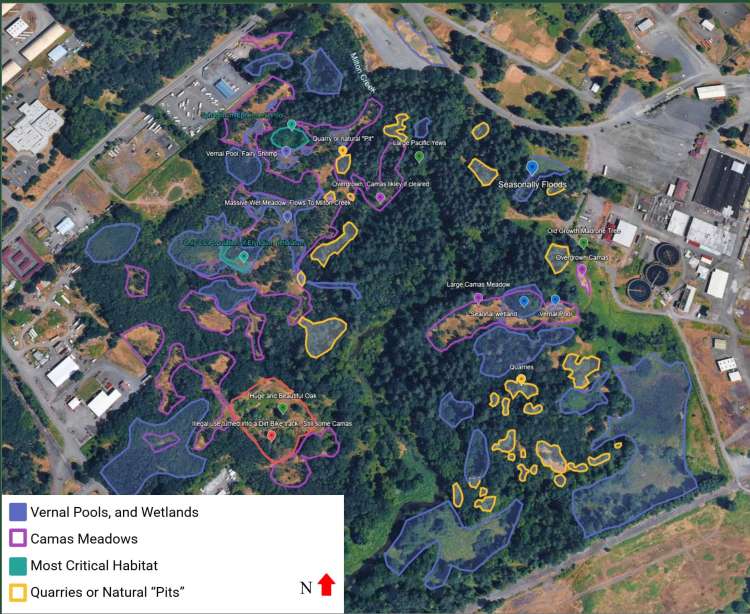

Lucas, who was a high school student at the time, had begun accompanying us on some surveys. We told him about the old Boise Cascade property and asked if he’d take it on as a special project. I think I may have hoped he’d go there 3-4 times, but soon he’d put in dozens of trips. What he found was an amazing matrix of vernal pools and camas meadows interspersed within riparian forest. He herped the first racer on the site, the first skink, and nearly all of the rarest plants we’ve recorded. Lucas’s personal observations allowed him to make the map above, and our knowledge of the biodiversity there relies heavily on the work he did.

This is what makes the property special:

Camas meadows

As we said above, an estimated 99.75% of the original camas meadows of the Willamette Valley have been destroyed. In Columbia County, we still have an amazing meadow at Liberty Hill, but that is threatened by development. Otherwise, camas is found in small patches near Columbia Botanical Gardens, Nob Hill Nature Park, McCormick Park, and a few minor lots. Only at Boise Cascade do we get a second example of full camas meadows, though they are still not nearly as large as Liberty Hill.

This is where the most interesting snakes and lizards of the property hang out, including rubber boas, racers, and western skinks. There are also Blacktail Deer, Douglas’s Ground Squirrels, and potentially additional rodents such as Camas Pocket Gophers and multiple species of voles.

The real treats are the wildflowers. Their diversity is incredible – likely over 100 species on this tiny property. Some of the rarest species that Lucas has found include Oblong Bluecurls, Alaskan Shooting Star, Nuttall’s Larkspur, Scatter Knotweed, and Oregon Coyote-Thistle. Each of these is rarely seen in the northern Willamette Valley, and in the case of the last two they appear to be the first records for Columbia County.

These plants support a vibrant insect population. There have not been any surveys yet, but nearby Liberty Hill has ~40 species of bees recorded, not to mention the butterflies, moths, beetles, and other insects that use these flowers.

Vernal pools

Spring rains cause vernal pools to pop up all over the basalt complex. The sheer volume and variety of wetlands on the property is extraordinary (look up at Lucas’s map again).

These pools are where amphibians like Long-toed Salamander, Rough-skinned Newt, Pacific Treefrog, and Northern Red-legged Frog breed.

We don’t have the expertise to investigate the invertebrate populations of the ponds, but they support many insect species along with smaller crustaceans like copepods and daphnia. Lucas has found Oregon Fairy Shrimp, an imperiled species known from fewer than 80 localities.

The rare Nuttall’s Quillwort, an unusual plant related to clubmosses (distant relatives of ferns), is found in these wet pools. Liberty Hill is the only other location in our region where they are known to exist. Meadow Bird’s Foot Trefoil, a wildflower that has been declining in Oregon, is found at the ponds’s edges.

Riparian forest

As amazing as I find the camas meadows and vernal pools, the forests might be my favorite part of the site. Where else in St. Helens can you find habitat that looks like this?

On the first trip, Matt found two Pacific Yew – a unique and vulnerable tree. The bark of this yew contains a cure for cancer, paclitaxel. In 2003, a means was found to synthetically manufacture the drug from other sources, necessary due to the tree’s rarity.

One of Lucas’s coolest finds was Mendocino Peatmoss – a rarely seen form of sphagnum moss found in only 3 other sites in the Willamette Valley. Nearby were Goldback Fern and Maidenhair Spleenwort, quite uncommon in the Willamette Valley.

The forests here and at adjacent McCormick Park are covered in Smallflower Wakerobin, an endangered trillium subspecies that is difficult to find outside of this immediate area. One estimate suggested there may be fewer than a thousand left in Oregon. That’s one of numerous wildflowers that can be found on the forest floor.

Only minimal bird walks have been completed, but the forests support many songbirds including Western Tanager, Cedar Waxwing, Hermit Thrush, Golden-crowned Kinglet, White-breasted Nuthatch, and warblers including Townsend’s, Black-throated Gray, Yellow-rumped, and Orange-crowned. A pair of Bald Eagles nest here every year. Townsend’s Chipmunks are abundant, and the ground cover likely includes a number of mole, shew and rodent species, possibly relative rarities such as American Shrew-mole and White-footed Vole.

Milton Creek

Last but not least, Milton Creek runs straight through the property, splitting the city-owned section from the port-owned section. We found Northern Red-legged Frogs and Rough-skinned Newts in the water, and verified reports of Western Painted Turtle using the creek to move between the Columbia River and upstream waters.

Milton Creek used to be the best Chum Salmon fishery in the region, but development decimated the lower portions of the creek where they spawn. Reports suggest that the narrowing of the channel, lack of deep pools, clearing of trees which led to warmer water, and degraded floodplain connectivity is responsible for this loss. It is possible the runs could be brought back if the creek and its floodplain were restored.

That same 2020 ODFW report found that Coho Salmon still come up the stream to spawn, along with lower numbers of Coastal Cutthroat Trout, Steelhead, and the occasional Chinook Salmon. Pacific Lamprey and Western Brook Lamprey were present as spawners as well. Significant restoration is needed to protect the remaining fish. The creek also has Peamouth Chub, Speckled Dace, Redside Shiner, Largescale Sucker, Banded Killifish, Three-spined Stickleback, and various sculpins (most likely Reticulate, Torrent, and Shorthead). Belted Kingfisher, Osprey, Bald Eagle, Great Blue Heron, Wood Ducks, and Common Merganser are among the birds that utilize the stream’s waters.

The presence of the creek would restrict any future industrial development, as the majority of the land is within 150 yards of the creek (before we even include the seasonal wetlands). There are required buffers alongside the creek as well as in the 100-year floodplain, plus a bend in the creek which creates a bottleneck on the port property, severely limiting how much land could be developed.

What’s the plan?

So what can be done here? As the City of St. Helens and Port of St. Helens already own the site, the solution is fairly simple. They could work together to set aside the land for a nature park. Trails and boardwalks can be built that make the area accessible to the public without damaging the habitat, similar to Camassia Nature Preserve in West Linn (or, at a much smaller scale, Nob Hill Nature Park). Information kiosks would educate the public on the plants, animals, geology and Indigenous history of the location.

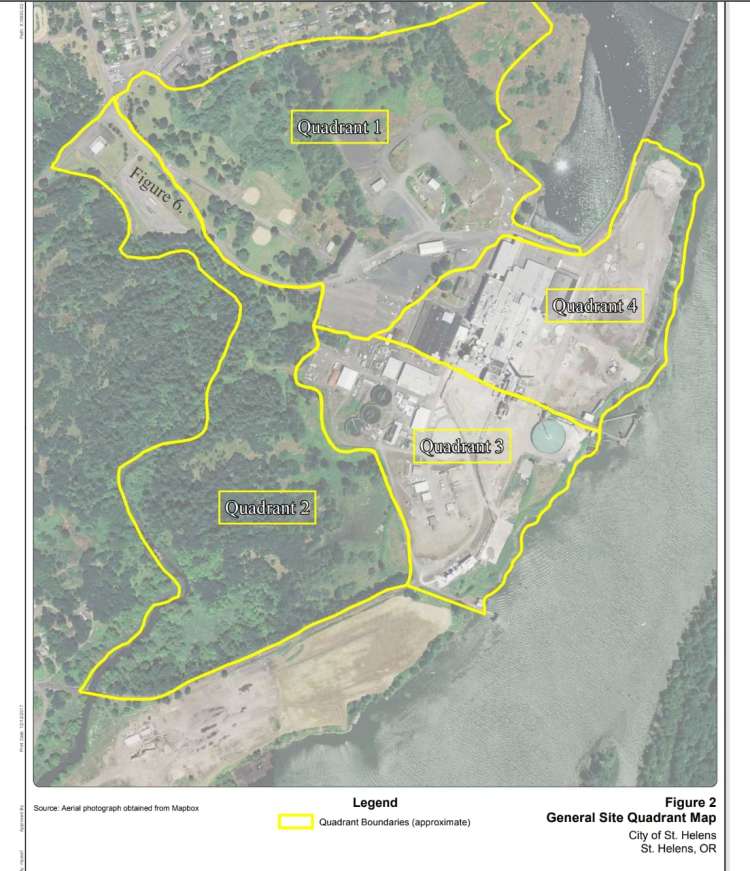

The land that we would want to preserve is only one quadrant of the former Boise Cascade property. It is the least useable portion of the land, as it is covered in wetlands, full of uneven rock formations, and has the stream which requires large buffers. Anyone who remembers the Christmas floods of ’64 or the February flood of ’96 knows that the entire parcel was under water both times. That will happen again. There are reasons that Boise Cascade never touched it in the decades they owned the property, reasons it was never developed by anyone else. We have better options.

The portion we would propose conserving is Quadrant 2, bordering the stream and infused with wetlands.

In addition to the other 3 quadrants of the St. Helens Industrial Park site, industrial development can be sited at the Armstrong World Industries site and the unused Port lots south of Walmart and adjacent to Trestle Beach. Industry has been slow to come back to St. Helens, and when it does come, we have places for it to go. We don’t need to wipe out one of the last remnants of a unique habitat when it would take tons of money and wetlands mitigation to open up any land at all to industry.

Look at the pictures. Take a walk at the site. With the right boardwalks and kiosks, its beauty will bring visitors. It would be the only wet meadow park in Columbia County. Families could combine it with play at McCormick Park to make a full afternoon out, and they buy food, gas, etc.

Even more important, it will bring more beauty to our own lives. More peace, more quiet, more time in nature that this tech-addicted era so desperately needs.

Species status for the animals and plants recorded at the site

Northern Red-legged Frog – ODFW Sensitive species, Oregon Conservation Strategy Species

Western Skink – one of only 3 populations known in Columbia County

Western Painted Turtle – ODFW Sensitive-Critical Species, Oregon Conservation Strategy Species, ORBIC List 2 (Threatened/Endangered in Oregon)

Bald Eagle nest – 330-foot buffer around nest required

Golden-crowned Kinglet – NatureServe Heritage S3 (Vulnerable in State)

White-breasted Nuthatch – NatureServe Heritage S3, ODFW Sensitive Species in Willamette Valley, Oregon Conservation Strategy Species

Chum Salmon – Federally Threatened, ODFW Sensitive-Critical Species, Oregon Conservation Strategy Species, ORBIC List 1 (Threatened/Endangered range-wide)

Coho Salmon – Federally Threatened, ODFW Endangered Species, Oregon Conservation Strategy Species, ORBIC List 1

Chinook Salmon – Federally Threatened, ODFW Sensitive-Critical Species, Oregon Conservation Strategy Species, ORBIC List 1

Steelhead – Federally Threatened, ODFW Sensitive-Critical Species, Oregon Conservation Strategy Species, ORBIC List 1

Coastal Cutthroat Trout – ODFW Sensitive Species, Oregon Conservation Strategy Species, ORBIC List 1

Pacific Lamprey – Federal Species of Concern, ODFW Sensitive Species, Oregon Conservation Strategy Species, ORBIC List 2

Western Brook Lamprey – Federal Species of Concern, ODFW Sensitive Species, Oregon Conservation Strategy Species

Oregon Fairy Shrimp – NatureServe Heritage S2 (imperiled in state), ORBIC List 2

Mendocino Peatmoss – Only found in 3 other sites in the Willamette Valley

Goldback Fern – uncommon in Willamette Valley

Maidenhair Spleenwort – uncommon in Willamette Valley

Nuttall’s Quillwort – rare in Willamette Valley, Natureserve Heritage S1 (critically imperiled) in Washington, not yet evaluated in Oregon

Small-flowered Trillium – NatureServe Heritage T2T3 (subspecies imperiled or vulnerable), ORBIC List 1 (threatened/endangered rangewide)

Small Camas and Great Camas – only 0.25% of original camas meadow remains in Willamette Valley

Oblong Bluecurls – rare in northern Oregon, assessment pending

Nuttall’s Larkspur – NatureServe Heritage S1 (critically imperiled in state), ORBIC List 2

Meadow Bird’s Foot Trefoil – declining in Oregon, NatureServe Heritage N2 (imperiled) in Canada

Fall Knotweed – First record in Columbia County, rare in north Willamette Valley

Oregon Coyote-Thistle – First record in Columbia County, rare range-wide

Alaskan Shooting Star – Subspecies is uncommon in western Oregon.

Great photos and wonderful write up!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You all do amazing work! I hope this meadow and oak forest can be set aside. Reach out if you need assistance.

LikeLiked by 1 person